|

My new collection of poetry and writing is available on Amazon, under my pen name of "Falcon Blackwood". It's the first collection of poems since "Traces" back in 2017. The subject matter is similar; quarries, industrial remains and all that (of course!) - except that this time there's a section on wider experiences from childhood. The blurb goes:

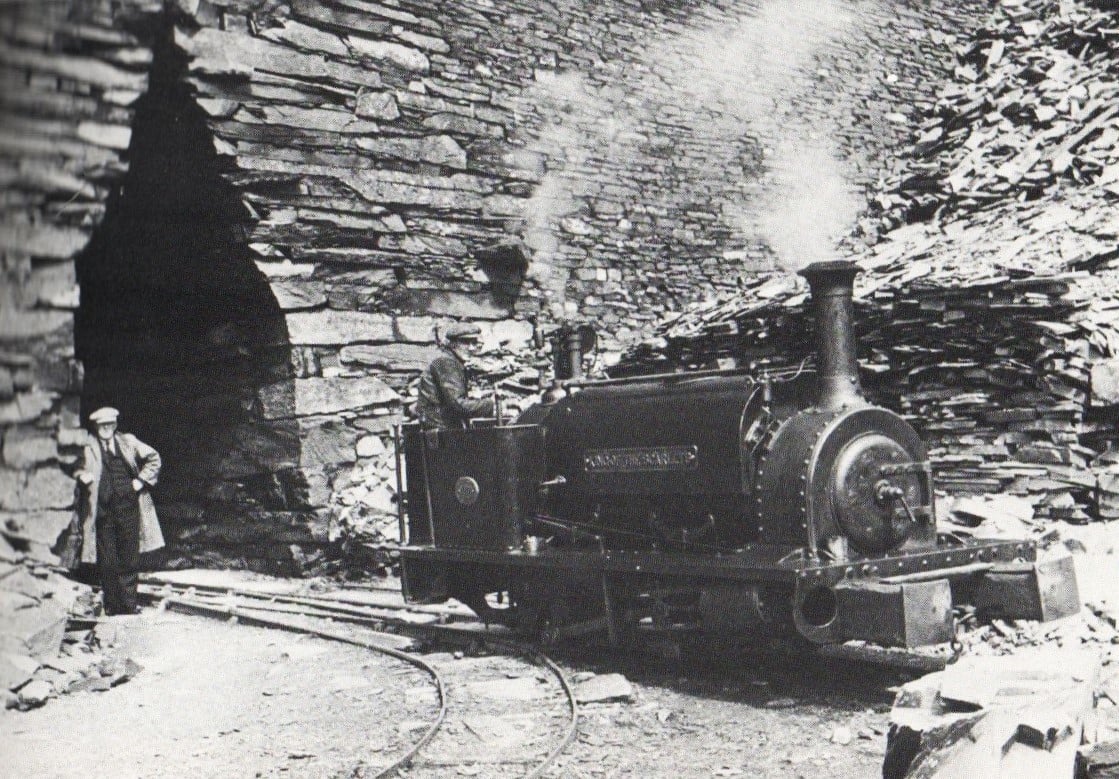

"A new collection of poems opens first with 'Passage', a section featuring works that explore relationships, how small, childish insights become tempered by time and experience. 'Curlews' tenderly laments the dissapearance of one of our favourite estuarine birds. 'Northbound' will resonate with anyone who has had to make a long, tedious motorway journey. In the second segment, 'Wales', the focus moves to the slate regions of the North with the historical exploitation of people and the landscape. Blackwood's love of Wales and his enthusiasm for the industrial vernacular shows through clearly, yet he manages to sidestep the obscure; the writing is always accessible and rewarding." "Bowden's Boat" is still in the editing stage, but I hope to have it out there very soon! This instalment of the Gorseddau Tramway saga starts from a handy access point, the farmyard at Cwrt Isaf (SH 53991 46403). There's a space to park a couple of cars and there used to be an honesty box- but lately I notice the farmhouse has been made into a holiday let; the farmyard had a desolate air. Anyway, we parked here recently and weren't challenged. The route up to Moel Hebog is also this way, over the ramshackle stile. The Afon Cwm-Llefrith runs to the right, but after striking up and over a few more dodgy stiles, an impressive bridge abutment signals the presence of the tramway. It's time to turn west. This must have been an imposing sight, with a short length of girder support spanning the gap. Next is a shallow, boggy cutting. The way here isn't strictly a footpath, but as it is on access land, I don't anticipate any trouble...we've been many times and haven't encountered any bother. The tramway curves north and begins it's steady progress towards the end of the cwm. There is much to see along the way; ruined cottages, beudys and consumption cairns, built to clear the land for agriculture. There are a few mediaeval house platforms, best found by consulting the Coflein maps. The careful construction of the tramway is evident all the way. There are some fine revetments, embankments and bridges... Thanks to my partner, Petra, for some of the above shots. Below are a selection of the relics along the way... I couldn't resist these two shots below, taken at vastly different times... Along the stretch from Cwrt Isaf, there is supposed to be a shaft from a mine to the west of the tramway. It will be a crown hole, nothing much will remain, but I've not seen it yet- it's probably grown over by vegetation. The tramway continues, over boggy waterlogged sections and dry causeways, keeping level for most of the way. Sometimes, incredibly, you can still see the depressions made by the sleepers in some places. Shortly after the beudy in the shot above, the tramway hooks a left and crosses a field, unusually an "improved" one. The line of the formation is almost lost, but it can be picked up again on the other side. Now things start to become impressive, with Moel Lefn beginning to soar above to the right. Impressive panoramas open up below and to the quarry at the end of the cwm. The tramway runs through a cutting before emerging into the mill area of the Prince of Wales quarry. To the east of the tramway, below Moel Lefn are a series of moraines. They are a stiff climb, but well worth the effort for the views they give. Below are a couple of shots on a winter's day, taken from the moraines, that emphasise the remoteness of the location... After the gate by the cutting, there is a bosky, small reservoir, shaded under trees. I don't know what the idea was, as the mill's power was from the reservoir in Cwm Trwsgl; perhaps water was so intermittent that the quarry builders needed to take every opportunity to keep the supply. Now the mill is reached. It's a fine structure with Brunellian arches and a large wheelpit. The incline to the Prince of Wales quarry goes up from this level. Of course, this was not the final destination of the tramway, that was Cwm Dwyfor, a little way further and higher. I have described this part of the route, and the quixotic mine that gave rise to it in my blog post here. Closure What of the fortunes of the tramway? Never illustrious and saddled with three ailing white elephant quarries throughout it's life, the tramway finally closed in around 1892. At some point, there had been a De Winton coffee pot locomotive ("Pert") used on parts of the line from 1874, but that was out of use by 1878 and most traffic on the tramway was horse (or man) hauled. "Pert" was sold on to a quarry in Nantlle Vale, probably Coedmadog. If you've managed this far, well that's about it for the Gorseddau Tramway. I'll leave you with some photos, and a note of the sources of information. BOYD, James I.C., Narrow Gauge Railways in South Caernarvonshire, vol.1, Oakwood, 1988, ISBN 0-85361-365-6, pp.6-46 RICHARDS, Alun John, A Gazeteer of the Welsh Slate Industry, Llanrwst: Carreg Gwalch, 1991, ISBN 0-86381-196-5, pp.93-104 Ben Fisher's excellent page about the tramway is here Some bonus pics:

This instalment continues on from part one, (at last!) where we’d only managed as far as Penmorfa. In fairness, there was a lot to see. This time, we’ll be heading out into the hills towards the Nantlle ridge and the steep slopes of Mynydd tal y Mignedd. First of all, you might like to refresh your memory with a look at a map someone has made of the whole length of the tramway here. By the way, my first post about the Porthmadog to Penmorfa section was here. Early Days Perhaps it was a tidy idea to end the first instalment where I did. Because in 1856, a plan was formed to extend the tramway out from Allt Wen, past Penmorfa towards the Gorseddau Quarry, some 3.6 kms away. The gauge of this enterprise was still 914mm (three feet) at this time, because it's precursor, the Tremadog Tramway was that gauge. Why not 610mm (two foot)? Well, partly because at that time, the Nantlle railway, north west of Porthmadog, had set the precedent at 914mm and was seen to be successful, running from Talysarn to Caernarfon*. The new outfit was called by the welsh name of the "Gorsedda" railway. It was engineered by James Brunlees, the man who also designed the superb Pont y Pandy mill. As we know, the Gorsedda quarry was an ailing concern pretty much from the off. It limped on for a few years until fading in 1867. But before the last rites were fully performed, the directors tried one last flourish of the pen in 1871 and announced that they would re-gauge the tramway, calling it the "Gorseddau Junction and Portmadoc(sic) railway". This made sense, as the tramway/railway now connected to the successful Croesor tramway and the Ffestiniog railway...except that there wasn't very much slate to be carried! Never mind, the line was authorised, and incorporated in 1871. A junction was made just past Braich y Big and the line headed off to what the promoters hoped would be it's saviour, The Prince of Wales Slate Quarry at the top of Cwm Pennant. (See the index on the right for my two posts about that amazing location.) The original formation to the Gorseddau Quarry remained at 914mm and became disused. The route. So let's have a look at what is left on the ground today. From where we last left the tramway, the route dives away on private land and disappears under the A487. But it emerges again shortly after and can be picked up as it crosses an old trackway that joins the A487 at Gorffwysta. The route can be accessed here- it's not a right of way and, technically, you are trespassing. But a couple of footpaths cross it, so you could make out a case for having lost your way. The formation is very overgrown in places, while elsewhere, it is still like a railway... The route is easy to trace on the map, or on Google Earth. It's also a pleasant reminder of how some things endure on the surface of the land, particularly in this part of the world. Here are a few more shots of the route just after Penmorfa... The formation is very boggy at the next line of fences, and becomes vestigial, being remembered only in field boundaries and hedge lines for a couple of kilometres, until it is crossed by a farm road at Gwernddwyryd. After this, it is lost beneath a grim caravan site and cement works at Glan Byl. It emerges on the other side of the A487 as firstly a line in the vegetation, then a hedgerow and finally a well revetted causeway across the marshy ground. This turns into a cutting past Cefn Peraidd as the ground starts to rise. Here there is a fascinating tunnel, which dives under the minor Penmorfa to Golan road. If you didn't know it was there, you wouldn't notice it, yet it is a fabulous survival. After the tunnel, we have another situation where the trackbed is private, although a couple of farm roads and a footpath cross it, so it's possible to see it and do a little exploration. Now the route is approaching the mill, Ty Mawr or Ynys y Pandy, whichever you prefer. Here, a footpath utilises the trackbed, giving some good views towards the wonderful remains of Ty Mawr. The mill is a destination in itself, and rewards some close scrutiny. I recommend the references in my blog post here for those interested enough to study the mysteries surrounding the place. At Braich y Big junction, the trackbed goes off to the right, north west towards the Gorseddau Quarry. Our route lies to the left, north westwards from Braich y Big along a footpath which stretches almost the whole way. The first few kilometres are fascinating for their views of Moel Isallt and the derelict farm of Caerfadog Uchaf. After Caerfadog Uchaf, the tramway describes a couple of tight scrolls to gain height. The country becomes a little more wild- at times it reminds me of the western states... Into the wilds The next section does seem a little wild west, especially in late summer when the grasses are a yellow brown colour. The route is fascinating, requiring many little accomodations with the land in the form of well-made small slate bridges or revetments. There are also a few Mediaeval house platforms and some fascinating examples of consumption cairns along the way, as if the stunning views weren't enough for you. A close shave It was along here that we had a lucky escape, as a young bull decided that we were a threat to his herd of heifers and charged us. I told to Petra to run for it, while I attempted to buy a little time and do what I'd seen my Dad do years ago on the farm. I stood with my arms wide and my stick ready, all the while shouting various curses at the bull. To my great relief, the fellow stopped and looked at me, puzzled, more than anything. But I was at least able to walk away backwards to the fence while he advanced at my pace. Luckily I didn't trip, and made it over the fence in one piece! Across the almost wild land here is a delight, no matter what the weather. As you can see from the photos, we've done it in all seasons; each has it's own charm, especially in the deep winter, when fox and rabbit tracks mingle with the sheep's hoofprints. You realise what a thoroughfare the tramway is for the creatures of the moor. Next instalment coming soon- Cwrt Isaf to the Prince of Wales Quarry.

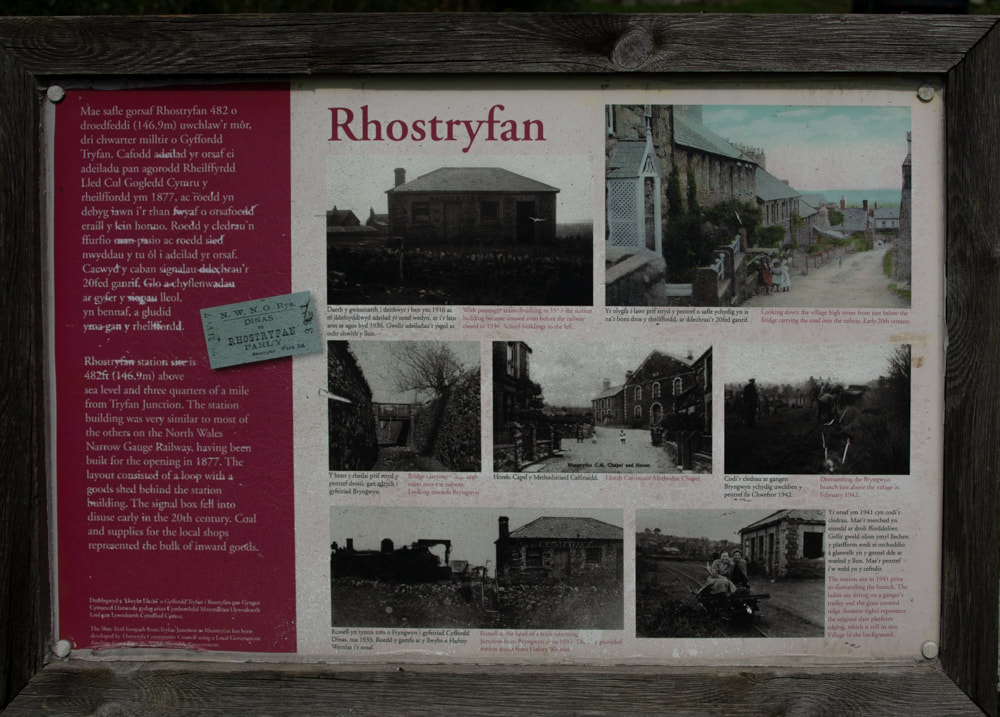

A look at the Bryngwyn Path This is a pleasant, bosky walking trail, which I suspect has the same bucolic feel about it as it did back in the nineteenth century when it was a narrow gauge railway. It follows the formation (for most of the way) of the old, disused Bryngwyn Branch of the Welsh Highland Railway. If you travel from the Tryfan junction end, towards Bryngwyn, there is a steady, if gentle, gradient uphill pretty much all the way. In an ideal world, you would get off the Welsh Highland train at the neat little Tryfan Junction station and walk up the trail from there. But we were being awkward, and started halfway along the route, doubling back. There’s a large car park at Rhostryfan (halfway point) which seems to be specifically for the trail, so this is where we left the car. Rhostryfan is signed from the main A487 which goes through Bontnewydd (not the new by-pass). Look out for a brown “Slate Trail” sign in the middle of Rhostryfan village. Walking the route, there are several old bridges, fulfilling their original purpose. It’s good that they haven’t had to fiddle about with altering the loading gauge or the ground levels because they didn’t have to cater for a modern railway like the W.H.R. You will soon begin to recognise the house-style of the bridges, with yellow brick arches and coursed stonework. Talking of relics, there are also one or two lengths of original rail in use as gateposts. The present footpath opened in May 2011- and with the passage of time, has lost it’s rawness and has settled nicely into the landscape. Mature trees line the route almost all the way until you start to see the quarries on the skyline. Towards the end of the trail, there are some curves which give panoramas of Caernarfon Bay and Anglesey, while the council web site claims that on a clear day, the Wicklow Mountains in Ireland can be seen in the distance. An unlooked-for bonus comes on the latter section of the route, as it starts to become more moorland in character. On the Caernarfon side of the trackbed are some Roman era hut circles, which can be made out by a rough ring of stones. They are difficult to see, and some to the Nantlle side are buried in gorse and bracken. But it’s quite a thought, to stand there and imagine folk settling here all those years ago. The only disappointment is that the route ends very suddenly at Bryngwyn farm. You can see the trackbed going off into the woods, but you can’t follow, as it’s private land. There’s no mention of this, or how to see the rest of the mile or so to the Bryngwyn Drumhead on the otherwise excellent signeage and interpretation boards. We ended up walking up the lane to the left, not realising that we were being shadowed by the trackbed as it looped and scrolled to gain height. The lane passes by some dwellings that were once humble quarryman’s smallholdings- apparently much of the trackbed is a right of way, and the incline itself crosses a “B” road and can be feintly made out with the eye of faith. If you intend to walk this section, it would be a good idea to take a map and have a good look at the Google Earth view as well. The site of Bryngwyn station has been obliterated, although Jaggers* says in his description “a more unlikely site for a railway station cannot be imagined. “ The council boast that the trail is a resource for cyclists- I doubt this, as the section from Rhostryfan to Bryngwyn is infested with gates, sometimes cropping up in groups of three. I suspect there were some hefty access issues and landowners to be placated; I understand that and it’s fine, but it’s not a cycle-friendly route, I don’t enjoy heaving my bike over endless gates. Once at the drumhead, the tramway split into three quite fascinating sections. All can be followed up to the quarries in one form or another. That’s an entirely different tale, and I hope to tell it soon. I’ve not gone into the history of the branch as it has been amply covered elsewhere, although I’ll give a few pointers below. Suffice to say that it opened in 1877 and was taken up in 1936. *Jaggers Heritage, PDF Welsh Highland Railway Bryngwyn Branch, an excellent site by Ben Fisher. The Bryngwyn Branch, out of print, but available on Ebay sometimes. Llanwnda community council site about the path Festipedia entry about the branch. "Mud and Routes", excellent description of the path. Here are some further photos of the branch.... In many ways, Dinorwig is shrouded in mystery. It can be frustrating not being able to find out what things are, why they are there and what their proper names are. Unfortunately for posterity, upon closure of the quarry in 1969 the management ordered that all records were to be destroyed- I can't help wondering just what they were trying to cover up. Some of the workers took quantities of the records home, rather than see them destroyed, and I'm so grateful to those enterprising folk. As for Morgan's level, nothing remains of it's history. A shame, since it is a landmark in the quarry. We know from the map evidence (Ordnance Survey XVII.NW) that Morgan's was working in 1888- the "Tank" incline that we see today is clearly marked, along with a line of "walliau" and other structures. The incline above, however, was already out of use. The Morgan incline (a "B" or local series incline in Dinorwig terms), starts at the Dyffryn Outlet tramway level. Rock was taken from this level to the mills at Ffiar Injan*. The incline is greatly degraded. Near the top, a fine set of steps can be used to reach the crimp, or platform. Until recently, the vestigial remains of a partial roof perched precariously above the Drumhouse, but the gales of 2021 saw that off. The drumhouse is interesting in that it has the brake drum on the outside of the building, similar to some of the drumhouses at Vivian. You can still see the braking mechanism and the levers which controlled it. One of the carriages, which held two waggons side by side, is still hanging precariously on the incline. The other must have been lost when the Dyffryn outlet tramway was converted to a haul road. There would have been a pit at the bottom to accomodate the carriage- this would have enabled the waggons to be rolled off and away to the mills. On this level to the rear of the drumhouse, there are some walliau and what look like a couple of offices. Behind and to the west of these is a tunnel that leads into Sinc Galed. This must have been relatively early in the life of the sinc, as the tunnel is marooned now and ends in a sheer drop of a couple of hundred feet. There's a dyke of whinstone running up the mountainside here, easily seen against the smooth slate measures to the side. At least the dyke was utilised to make the foxes path, that was something. So it's time to ascend the second Morgan's incline. But before we do, let's go around to the eastern side of the lower Morgan's workings, where there is a Ponc (bank) above the Dyffryn workings. I mentioned Whinstone dykes, well there are a couple of crackers in here. The quarrymen didn't have it all their own way, as can be seen from this vantage point. The second incline is in surprisingly good condition considering that it has been abandoned for at least 142 years. As with everything at Dinorwig, it is a masterpiece of dry stone wall building, a real monument to these incredible men. While I'm talking about the men, we had stopped earlier in the Dyffryn twll to have breakfast and I ruminated on the thought that this vast opening in the mountain was nothing compared to the Garret twlls, or the silences of the Braich or Twll Mawr. Yet it must have taken several generations of men to carve it out. What a thought. We walked up the incline and I became aware of a piquant whiff coming from somewhere. I looked behind me to see a goat patiently following, stopping when I stopped and looking at me as if to say "What? Come on, move it, pal!" Reaching the top, he quickly moved on past, following his own goaty agenda. The top of this incline is a shattered, seemingly ancient world. Old shelters hang on to the mountainside and an office complex teeters over it all. This level, which seems to be the upper limit of access in quarry terms from Morgan's, leads into the side of Sinc Braich, or the "Lost World" as the climbers call it. So perhaps this smaller digging might be Sinc Braich Bach. Probably an early, exploratory or development level of the main Braich twll. It has some remnants of air piping remaining and a few waggon bits, but looks like a working that was abandoned long ago. There are, however, some amazing views into Braich... If you were to struggle on upwards from here, you would come to Bonc Roller and Pen Garret. But for now, we will leave Morgan's and it's mysteries for another time.

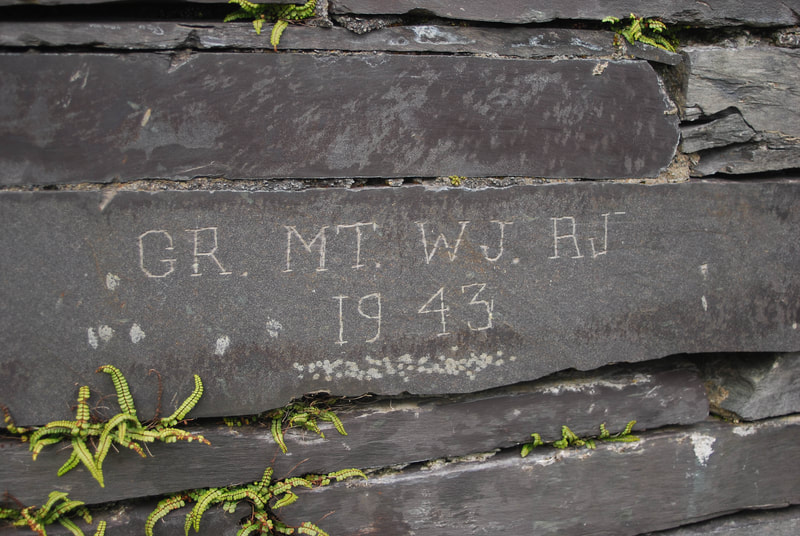

If anyone does know more about these fascinating levels, I would love to know. *Ffiar Injan mills was the name given to a steam engine that powered the mills on the A4 level (Harriet). The engine was made by David Bros, Sheffield. Dinorwig's owner, Thomas Assheton Smith, in his vainglorious book "The reminiscences of a famous foxhunter" says that: "The steam engine has been worked ten years both day and night yet it has never been known to be out of order. The quarrymen have such faith in it that they affirm it would work just as well on slates as on coal and coke." It's a wonder Assheton Smith didn't insist the men tried that. References: The usual suspects: Dinorwic (sic) by Reg Chambers Jones, Bridge Books, ISBN: 1-84494-033-0 Slates to Velinhelli (sic) D C Carrington and T F Rushworth, Maid Marian Locomotive Fund, 1972. Delving in Dinorwig, Douglas C Carrington, Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 1994, ISBN: 0-86381-285-6 Observations from photographs by Eric Jones Finally, some photos that wouldn't fit anywhere else... Before the ubiquitous diesel truck, most quarries of any size boasted a couple of locomotives to shunt waggons around their internal tramways, taking rubbish to the tips, or rock to the mill. Of course, those locos needed somewhere out of the weather to shelter overnight, or be worked on. This was never more important than at Dinorwig, where the prospect of doing maintenance, out of doors, on a steam locomotive didn't seem like a very inviting idea. Most of the galleries are in exposed locations, and a good many of them are over the 1,000 foot contour line, right in the way of those snell Snowdonian winds. The locos didn't just shelter overnight either- they had major repairs done to them on the galleries. The prospect of lowering a loco down the inclines to the works at Gilfach Ddu was not something to be taken lightly. Quite apart from the danger inherent with such an operation, the locos had to be stripped down and their motion removed to ride the inclines...reading some accounts, it seemed a risky business, one better to be avoided unless absolutely necessary. So it was that some locos stayed up in their lofty eyries for thirty years before going down to the works for overhaul. Perhaps a pretty major one, though- after 30 years of continuous use!  Australia shed, 1600 feet up a mountain! Here it was that "Alice" lay for many years. She was in company with "Irish Mail" for a while, and before that, between 1930 and 1945, "Maid Marian". There's a photograph in Boyd's book (see bibliography) of Alice resting in this shed from almost the same angle. On a gallery in the Braich district like Pen Garret, the rubbish runs were nearly a mile long and then there was rock to be removed in "Car Cryn" (slab wagons) to the top of the incline and rubbish to be marshalled in "Wagan Dipio". Plus sorting, shunting and...derailing. This latter was not an unusual occurrence; wagons would fall off the indifferent trackwork, at which point the loco crew would have to get off their steed and reform the errant vehicle with crowbar and some basic Welsh invocations. Usually other quarrymen would pitch in and help, especially if it was the loco that had lost her feet- after all, a delay in sending slate to the mill or rubbish to the tip affected everyone's pockets. The loco drivers always reckoned that they were the fittest men in the quarry with all the running about, heaving couplings and chains, pulling point levers and, of course, re-railing. I haven't uncovered all the sheds yet, there are some which have been lost forever (such as the one on Hafod Owen) and and in any case, this doesn't purport to be an exhaustive account. For instance, I've not mentioned the shed at Vivian which housed the original Horlock locomotive...more of that soon.  Lernion shed, in the Braich district. This was the highest shed in the British Isles, at over 1800 feet above sea level. Draughty... definitely a case of the thermals in winter! "Michael was resident here from 1931 until1945, then "Red Damsel" and finally "Holy War" until 1960 when moved to Penrhydd Bach. I've not spoken much about the locomotives, thinking that most folk are familiar with them...Hunslet, mostly... small, pesky but rather cute...the Jack Russells of the loco world. If this doesn't ring a bell, then you are most fortunate and have a wonderful journey of discovery ahead- I have provided references at the end. The other wonderful thing is that many of the latter-day locomotives are still with us, working on preserved railways up and down the country. Indeed, most have been in preservation for longer than they were working, but I really don't want to go into that! I tend to think of them as old friends, as I have been reading about them and looking for them since my teens (not yesterday) -I always have a few misty moments when encountering them in their new habitats, where I am sure they are less taxed. Most of the sheds in the quarry were self-contained and followed a pattern- there would be two slate pillars outside the front doors with a strong girder between them, which would act as a support for pulley blocks to lift the loco off it's wheels, or remove the boiler. Inside, there would be a pit, essential for inspecting and working on the motion, for valve setting and generally oiling and checking things. Some of the sheds had a store attached for essential spares like firebars etc and to keep coal dry. Others had a caban, as at Penrhydd Bach. Or sometimes there was a tandem shed, as at Pen Garret. All were made of slate. There were other sheds around the quarry for locomotives to shelter in during blasting operations, as damage to a loco could be expensive in materials and man-hours, let alone the dire consequences of having to explain the damage to management. These sheds are in the form of simple open-ended shelters, like a very over-engineered car port.  There's a photo of this structure in J.I.C. Boyd's book on the quarry, which he captions: "In such shelters as these, locomotives might lurk during blasting operations..." Pen Garret level, Dinorwig. Boyd's photo is from the other side, looking towards Garret and is an interesting study, if you have the book. Of the locomotives themselves, most galleries had one or two, and they were crewed by the same folk for years on end. An older man would be the driver, with a young lad, or teenager as the "fireman"/shunter/tea brewer/general gopher. Many young lads had the opportunity to join family members in a "bargen" with a team of rockmen, or work in the mill, but a surprising number wanted to crew the little locos. It wasn't really a popular choice with the other lads, as it was seen as a sinecure and rather unskilled. Mickey-taking could ensue. The wages were a little lower to begin with, and there was always the matter of waiting for dead men's shoes. The little Hunslets certainly are easy to drive- I have spent a couple of very enjoyable days abusing slate trucks with "Lilla" and can vouch for that- but factor in all the things you would have to know about the sometimes labyrinthine working practices and the unexpected events on the galleries and I don't think it was such a pushover. Plus, the locos had to be lit up an hour and a half before work started, which meant climbing the endless steps up the Foxes' Path, for instance to Australia level, well before even the quarrymen had flung a leg out of bed. Unlike in other quarries, there are some first-hand records from the drivers and other quarrymen concerning the working and stabling of the locos, and these can be discovered in the books listed at the end of the post. In the early days, the drivers were encouraged to take a pride in the locos by a system of bonuses and a sort of league table. Those that failed in this endeavour were generally ill-regarded and could be turfed off the job if they didn't mend their ways and buy some Brasso. Even in the fifties, photographs of the locos show them to be well cared for and clean in most examples. Much later in the quarry's story, there is the poignant moment in the lives of the sheds when they were abandoned by their tenants, who were never to return. Some, like Alice on Australia level, stayed for a long time after closure. In the sixties, early on in the preservation movement, most thought it was too big a project to rescue her and send her down the now sketchy inclines, although other engines, like "Michael" did take the plunge. It was left to members of the West Lancashire Light Railway group to perform the rescue operation in 1972, where the RAF and their Chinook Helicopter had failed before them. The full story can be read in Cliff Thomas's excellent book...suffice to say that she is now restored and has even had some trips abroad! Douglas Carrington's book also has some wonderful accounts and photos of other loco rescue operations at Dinorwig. It's nice to happen upon previously unfamiliar photographs of the locos in their sheds at the quarry, and scrutinise them before realising where the location is, whereupon a warm glow of recognition permeates the sentimental mechanisms of this old ferroequinologist. I have particularly enjoyed finding the locations in Boyd's photographs. Finding little bits of graffiti from the thirties and forties is also very rewarding, even if it is sometimes scrawled over by the ill-educated churls who wander the galleries in search of things to throw. Finally, I noted something special at the last shed I visited, at Pen Garret on the Braich tip runs. The shed was approached by a cinder path, something that will chime with railway enthusiasts of a certain age who remember bunking BR loco sheds. That the cinders were without doubt from steam locomotive fireboxes was almost too nostalgic to contemplate, especially as soon afterward I made the discovery of some old firebars, lying in a pile where they had been discarded probably sixty years ago. In conclusion, if you have a sympathy for small, impudent steam locomotives and a love of quarries, visit Dinorwig. Go quietly and please don't throw or displace anything. Just stand and feel the little iron ghosts around you as they chuff fussily about the galleries. Some further reading: "Quarry Hunslets of North Wales - The Great `Little` Survivors" 1st Edition - August 2001 by Cliff Thomas ISBN 0853615756 Book Hardback 256 Pages 200 B&W Photographs Publisher: Oakwood Press "Narrow Gauge Railways in North Caernarvonshire - Volume 3" 1st Edition - Reprinted 2001 by James I C Boyd ISBN 0853613281 Book Hardback 336 Pages Publisher: Oakwood Press Series: British Narrow Gauge Railway "Delving in Dinorwig" by Douglas Carrington, ISBN: 9780863812859 (0863812856) Publication Date January 2004 Publisher: Llygad Gwalch Cyf, Llanrwst Format: Paperback, 92 pages "Dinorwic: The Llanberis Slate Quarry, 1780-1969" Reg Chambers Jones ISBN: 978-1-844940-33-2 Bridge Books "Slates to Velinheli" The Railways of Tramways of Dinorwic Slate Quarries Llanberis Published by Maid Marian Locomotive Fund Written by D. C. Carrington and T. F. Rushworth "Up there

between the mist wraiths the iron ghosts rumble occasionally peering from tunnels spooking the goats" |

TracksReceive the occasional Treasure Maps Newsletter- and alerts when a new post is available!

If you enjoy my content, please buy me a coffee!

Check out my other online activity...

Index

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed